I’m going to start this post with an excerpt from the book “Constructing the User Interface with Statecharts”, written by Ian Horrocks in 1999:

User interface development tools are very powerful. They can be used to construct large and complex user interfaces, with only a relatively small amount of code written by an application developer. And yet, despite the power of such tools and the relatively small amount of code that is written, user interface software often has the following characteristics:

- the code can be difficult to understand and review thoroughly:

- the code can be difficult to test in a systematic and thorough way;

- the code can contain bugs even after extensive testing and bug fixing;

- the code can be difficult to enhance without introducing unwanted side-effects;

- the quality of the code tends to deteriorate as enhancements are made to it.

Despite the obvious problems associated with user interface development, little effort has been made to improve the situation. Any practitioner who has worked on large user interface projects will be familiar with many of the above characteristics, which are symptomatic of the way in which the software is constructed.

In case you didn’t do the math, this was written over 20 years ago and yet it echoes the same sentiments that many developers feel today about the state of app development. Why is that?

We’ll explore this with a simple example: fetching data in a React component. Keep in mind, the ideas presented in this article are not library-specific, nor framework-specific… in fact, they’re not even language specific!

Trying to make fetch() happen

Suppose we have a DogFetcher component that has a button that you can click to fetch a random dog. When the button is clicked, a GET request is made to the Dog API, and when the dog is received, we show it off in an <img /> tag.

A typical implementation with React Hooks might look like this:

function DogFetcher() {

const [isLoading, setIsLoading] = useState(false);

const [dog, setDog] = useState(null);

return (

<div>

<figure className="dog">{dog && <img src={dog} alt="doggo" />}</figure>

<button

onClick={() => {

setIsLoading(true);

fetch(`https://dog.ceo/api/breeds/image/random`)

.then((data) => data.json())

.then((response) => {

setDog(response.message);

setIsLoading(false);

});

}}

>

{isLoading ? "Fetching..." : "Fetch dog!"}

</button>

</div>

);

}

This works, but there’s one immediate problem: clicking the button more than once (while a dog is loading) will display one dog briefly, and then replace that dog with another dog. That’s not very considerate to the first dog.

The typical solution to this is to add a disabled={isLoading} attribute to the button:

function DogFetcher() {

// ...

<button

onClick={() => {

// ... excessive amount of ad-hoc logic

}}

disabled={isLoading}

>

{isLoading ? "Fetching..." : "Fetch dog!"}

</button>;

// ...

}

This also works; you’re probably satisfied with this solution. Allow me to burst this bubble.

What can possibly go wrong?

Currently, the logic reads like this:

When the button is clicked, fetch a new random dog, and set a flag to make sure that the button cannot be clicked again to fetch a dog while one is being fetched.

However, the logic you really want is this:

When a new dog is requested, fetch it and make sure that another dog can’t be fetched at the same time.

See the difference? The desired logic is completely separate from the button being clicked; it doesn’t matter how the request is made; it only matters what logic happens afterwards.

Suppose that you want to add the feature that double-clicking the image loads a new dog. What would you have to do?

It’s all too easy to forget to add the same “guard” logic on figure (after all, <figure disabled={isLoading}> won’t work, go figure), but let’s say you’re an astute developer who remembers to add this logic:

function DogFetcher() {

// ...

<figure

onDoubleClick={() => {

if (isLoading) return;

// copy-paste the fetch logic from the button onClick handler

}}

>

{/* ... */}

</figure>

// ...

<button

onClick={() => {

// fetch logic

}}

disabled={isLoading}

>

{/* ... */}

</button>

// ...

}

In reality, you can think about this as any use-case where some sort of “trigger” can happen from multiple locations, such as:

- a form being able to be submitted by pressing “Enter” in an input or clicking the “Submit” button

- an event being triggered by a user action or a timeout

- any app logic that needs to be shared between different platforms with different event-handling implementations (think React Native)

But there’s a code smell here. Our same fetch logic is implemented in more than one place, and understanding the app logic requires developers to jump around in multiple parts of the code base, finding all of the event handlers where there are tidbits of logic and connecting them together mentally.

DRYing up the splashes of logic

Okay, so putting logic in our event handlers is probably not a good idea, but we can’t exactly put our finger on the reason why yet. Let’s move the fetch logic out into a function:

function DogFetcher() {

const [isLoading, setIsLoading] = useState(false);

const [dog, setDog] = useState(null);

function fetchDog() {

if (isLoading) return;

setIsLoading(true);

fetch(`https://dog.ceo/api/breeds/image/random`)

.then((data) => data.json())

.then((response) => {

setDog(response.message);

setIsLoading(false);

});

}

return (

<div>

<figure className="dog" onDoubleClick={fetchDog}>

{dog && <img src={dog} alt="doggo" />}

</figure>

<button onClick={fetchDog}>

{isLoading ? "Fetching..." : "Fetch dog!"}

</button>

</div>

);

}

Adding features and complexity

Now let’s see what happens when we want to add basic “features”, such as:

- If fetching a dog fails, an error should be shown.

- Fetching a dog should be cancellable.

I hesitate to call these “features” because these types of behaviors should be naturally enabled by the programming patterns used, but let’s try to add them anyhow:

function DogFetcher() {

const [isLoading, setIsLoading] = useState(false);

const [error, setError] = useState(null);

const [canceled, setCanceled] = useState(false);

const [dog, setDog] = useState(null);

function fetchDog() {

setCanceled(false);

setError(null);

setIsLoading(true);

fetchRandomDog()

.then((response) => {

// This should work... but it doesn't!

if (canceled) return;

setIsLoading(false);

setDog(response.message);

})

.catch((error) => {

setIsLoading(false);

setCanceled(false);

setError(error);

});

}

function cancel() {

setIsLoading(false);

setCanceled(true);

}

return (

<div>

{error && <span style={{ color: "red" }}>{error}</span>}

<figure className="dog" onDoubleClick={fetchDog}>

{dog && <img src={dog} alt="doggo" />}

</figure>

<button onClick={fetchDog}>

{isLoading ? "Fetching..." : "Fetch dog!"}

</button>

<button onClick={cancel}>Cancel</button>

</div>

);

}

This looks like it should work -- all of our Boolean flags are being set to the correct values when things happen. However, it does not work because of a hard-to-catch bug: stale callbacks. In this case, the canceled flag inside the .then(...) callback will always be the previous value instead of the latest canceled value, so cancelling has no effect until the next time we try to fetch a dog, which isn’t what we want.

Hopefully you can see that even with these simple use-cases, our logic has quickly gone out-of-hand, and juggling Boolean flags has made the logic buggier and harder to understand.

Reducing complexity effectively

Instead of haphazardly adding Boolean flags everywhere, let’s clean this up with the useReducer and useEffect hooks. These hooks are useful because they express some concepts that lead to better logic organization:

- The

useReducerhook uses reducers, which return the next state given the current state and some event that just occurred. - The

useEffecthook synchronizes effects with state.

To help us organize the various app states, let’s define a few and put them under a status property:

- An

"idle"status means that nothing happened yet. - A

"loading"status means that the dog is currently being fetched. - A

"success"status means that the dog was successfully fetched. - A

"failure"status means that an error occurred while trying to fetch the dog.

Now let’s define a few events that can happen in the app. Keep in mind: these events can happen from anywhere, whether it’s initiated by the user or somewhere else:

- A

"FETCH"event indicates that fetching a dog should occur. - A

"RESOLVE"event with adataproperty indicates that a dog was successfully fetched. - A

"REJECT"event with anerrorproperty indicates that a dog was unable to be fetched for some reason. - A

"CANCEL"event indicates that an in-progress fetch should be canceled.

Great! Now let’s write our reducer:

function dogReducer(state, event) {

switch (event.type) {

case "FETCH":

return {

...state,

status: "loading",

};

case "RESOLVE":

return {

...state,

status: "success",

dog: event.data,

};

case "REJECT":

return {

...state,

status: "failure",

error: event.error,

};

case "CANCEL":

return {

...state,

status: "idle",

};

default:

return state;

}

}

const initialState = {

status: "idle",

dog: null,

error: null,

};

Here’s the beautiful thing about this reducer. It is completely framework-agnostic - we can take this and use it in any framework, or no framework at all. And that also makes it much easier to test.

But also, implementing this in a framework becomes reduced (pun intended) to just dispatching events. No more logic in event handlers:

function DogFetcher() {

const [state, dispatch] = useReducer(dogReducer, initialState);

const { error, dog, status } = state;

useEffect(() => {

// ... fetchDog?

}, [state.status]);

return (

<div>

{error && <span style={{ color: "red" }}>{error}</span>}

<figure className="dog" onDoubleClick={() => dispatch({ type: "FETCH" })}>

{dog && <img src={dog} alt="doggo" />}

</figure>

<button onClick={() => dispatch({ type: "FETCH" })}>

{status === "loading" ? "Fetching..." : "Fetch dog!"}

</button>

<button onClick={() => dispatch({ type: "CANCEL" })}>Cancel</button>

</div>

);

}

However, the question remains: how do we execute the side-effect of actually fetching the dog? Well, since the useEffect hook is meant for synchronizing effects with state, we can synchronize the fetchDog() effect with status === 'loading', since 'loading' means that that side-effect is being executed anyway:

// ...

useEffect(() => {

if (state.status === "loading") {

let canceled = false;

fetchRandomDog()

.then((data) => {

if (canceled) return;

dispatch({ type: "RESOLVE", data });

})

.catch((error) => {

if (canceled) return;

dispatch({ type: "REJECT", error });

});

return () => {

canceled = true;

};

}

}, [state.status]);

// ...

The fabled "disabled" attribute

The logic above works great. We’re able to:

- Click the “Fetch dog” button to fetch a dog

- Display a random dog when fetched

- Show an error if the dog is unable to be fetched

- Cancel an in-flight fetch request by clicking the “Cancel” button

- Prevent more than one dog from being fetched at the same time

…all without having to put any logic in the <button disabled={...}> attribute. In fact, we completely forgot to do so anyway, and the logic still works!

This is how you know your logic is robust; when it works, regardless of the UI. Whether the “Fetch dog” button is disabled or not, clicking it multiple times in a row won’t exhibit any unexpected behavior.

Also, because most of the logic is delegated to a dogReducer function defined outside of your component, it is:

- easy to make into a custom hook

- easy to test

- easy to reuse in other components

- easy to reuse in other frameworks

The final result

Change the <DogFetcher /> version in the select dropdown to see each of the versions we've explored in this tutorial (even the buggy ones).

Pushing effects to the side

There’s one lingering thought, though… is useEffect() the ideal place to put a side effect, such as fetching?

Maybe, maybe not.

Honestly, in most use-cases, it works, and it works fine. But it’s difficult to test or separate that effect from your component code. And with the upcoming Suspense and Concurrent Mode features in React, the recommendation is to execute these side-effects when some action triggers them, rather than in useEffect(). This is because the official React advice is:

If you’re working on a data fetching library, there’s a crucial aspect of Render-as-You-Fetch you don’t want to miss. We kick off fetching before rendering.

https://reactjs.org/docs/concurrent-mode-suspense.html#start-fetching-early

This is good advice. Fetching data should not be coupled with rendering. However, they also say this:

The answer to this is we want to start fetching in the event handlers instead.

This is misleading advice. Instead, here's what should happen:

- An event handler should send a signal to “something” that indicates that some action just happened (in the form of an event)

- That “something” should orchestrate what happens next when it receives that event.

Two possible things can happen when an event is received by some orchestrator:

- State can be changed

- Effects can be executed

All of this can happen outside of the component render cycle, because it doesn't necessarily concern the view. Unfortunately, React doesn't have a built-in way (yet?) to handle state management, side-effects, data fetching, caching etc. outside of the components (we all know Relay is not commonly used), so let's explore one way we can accomplish this completely outside of the component.

Using a state machine

In this case, we're going to use a state machine to manage and orchestrate state. If you're new to state machines, just know that they feel like your typical Redux reducers with a few more "rules". Those rules have some powerful advantages, and are also the mathematical basis for how literally every computer in existence today works. So they might be worth learning.

I'm going to use XState and @xstate/react to create the machine:

import { Machine, assign } from "xstate";

import { useMachine } from "@xstate/react";

// ...

const dogFetcherMachine = Machine({

id: "dog fetcher",

initial: "idle",

context: {

dog: null,

error: null,

},

states: {

idle: {

on: { FETCH: "loading" },

},

loading: {

invoke: {

src: () => fetchRandomDog(),

onDone: {

target: "success",

actions: assign({ dog: (_, event) => event.data.message }),

},

onError: {

target: "failure",

actions: assign({ error: (_, event) => event.data }),

},

},

on: { CANCEL: "idle" },

},

success: {

on: { FETCH: "loading" },

},

failure: {

on: { FETCH: "loading" },

},

},

});

Notice how the machine looks like our previous reducer, with a couple of differences:

- It looks like some sort of configuration object instead of a switch statement

- We’re matching on the state first, instead of the event first

- We’re invoking the

fetchRandomDog()promise inside the machine! 😱

Don’t worry; we’re not actually executing any side-effects inside of this machine. In fact, dogFetcherMachine.transition(state, event) is a pure function that tells you the next state given the current state and event. Seems familiar, huh?

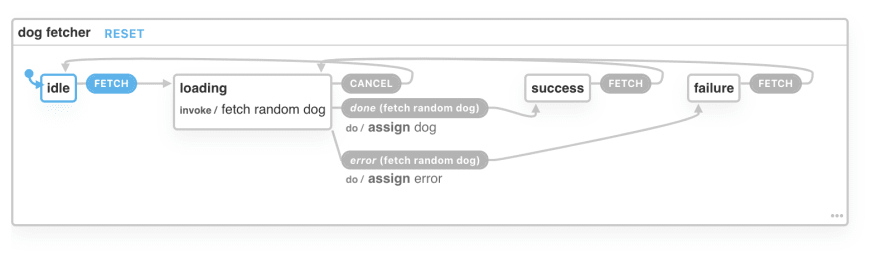

Furthermore, I can copy-paste this exact machine and visualize it in XState Viz:

View this viz on xstate.js.org/viz

So what does our component code look like now? Take a look:

function DogFetcher() {

const [current, send] = useMachine(dogFetcherMachine);

const { error, dog } = current.context;

return (

<div>

{error && <span style={{ color: "red" }}>{error}</span>}

<figure className="dog" onDoubleClick={() => send("FETCH")}>

{dog && <img src={dog} alt="doggo" />}

</figure>

<button onClick={() => send("FETCH")}>

{current.matches("loading") && "Fetching..."}

{current.matches("success") && "Fetch another dog!"}

{current.matches("idle") && "Fetch dog"}

{current.matches("failure") && "Try again"}

</button>

<button onClick={() => send("CANCEL")}>Cancel</button>

</div>

);

}

Here’s the difference between using a state machine and a reducer:

- The hook signature for

useMachine(...)looks almost the same asuseReducer(...) - No fetching logic exists inside the component; it’s all external!

- There’s a nice

current.matches(...)function that lets us customize our button text send(...)instead ofdispatch(...)... and it takes a plain string! (Or an object, up to you).

A state machine/statechart defines its transitions from the state because it answers the question: “Which events should be handled from this state?” The reason that having <button disabled={isLoading}> is fragile is because we admit that some “FETCH” event can cause an effect no matter which state we’re in, so we have to clean up our ~mess~ faulty logic by preventing the user from clicking the button while loading.

Instead, it’s better to be proactive about your logic. Fetching should only happen when the app is not in some "loading" state, which is what is clearly defined in the state machine -- the "FETCH" event is not handled in the "loading" state, which means it has no effect. Perfect.

Final points

Disabling a button is not logic. Rather, it is a sign that logic is fragile and bug-prone. In my opinion, disabling a button should only be a visual cue to the user that clicking the button will have no effect.

So when you’re creating fetching logic (or any other kind of complex logic) in your applications, no matter the framework, ask yourself these questions:

- What are the concrete, finite states this app/component can be in? E.g., "loading", "success", "idle", "failure", etc.

- What are all the possible events that can occur, regardless of state? This includes events that don't come from the user (such as

"RESOLVE"or"REJECT"events from promises) - Which of the finite states should handle these events?

- How can I organize my app logic so that these events are handled properly in those states?

You do not need a state machine library (like XState) to do this. In fact, you might not even need useReducer when you’re first adopting these principles. Even something as simple as having a state variable representing a finite state can already clean up your logic plenty:

function DogFetcher() {

// 'idle' or 'loading' or 'success' or 'error'

const [status, setStatus] = useState("idle");

}

And just like that, you’ve eliminated isLoading, isError, isSuccess, startedLoading, and whatever Boolean flags you were going to create. And if you really start to miss that isLoading flag (for whatever reason), you can still have it, but ONLY if it’s derived from your organized, finite states. The isLoading variable should NEVER be a primary source of state:

function DogFetcher() {

// 'idle' or 'loading' or 'success' or 'error'

const [status, setStatus] = useState("idle");

const isLoading = status === "loading";

return (

// ...

<button disabled={isLoading}>{/* ... */}</button>

// ...

);

}

And we’ve come full circle. Thanks for reading.